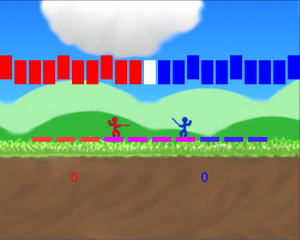

The entire team is currently here in San Francisco for the Game Developer’s Conference. In the last few weeks, we’ve been focusing on adding in a few final features and polishing existing features so that we have something really great to present at the conference. Controllers are no longer necessary to play, as we’ve added in keyboard support. Our tutorial level has been refined to be a bit more intuitive, and players can now navigate through the ether to reach other levels after exiting the tutorial area. Now that we’re here, we’re all quite happy with the current state of Amirelia, and we are really looking forward to displaying it during tomorrow’s prototype/playtesting event. Based on the feedback we receive from the playtests, we’ll make changes and document them here as we make progress.

Summary Update

While we’ve been doing a fair amount of documenting since our last update way back in October, we haven’t been updating the blog. So here’s a brief summary of the progress we’ve made since then:

Back in November, we finally finished narrowing down our focus and decided that we wanted to have the experience revolve around friendship and how friends rely on one another. Mechanically, we decided to convey this by having the players connect with a physical, visible bond between them.

As we developed throughout November and into December, we added more mechanics that encouraged players to be connected by a bond, and more importantly, to generally work together. We felt that there were a number of cooperative games out there that don’t really require cooperation, but rather act like a single player game that can be played by two people. So we designed our levels and puzzles to encourage cooperation in a variety of ways.

Over the winter break and since the start of this spring semester, we’ve all had our eyes set on GDC, the Game Developer’s Conference in San Francisco. We have focused our efforts to make sure that we have a satisfying experience for people to try out when we go there. That’s where we’re at for the moment, and we will continue to update as time provides in the coming weeks.

Trust Climber: Some Final Thoughts

We got to a point with Trust Climber where it sort of does what we wanted it to do; a two player game in which there is one climber and one belayer. The belay has to give slack or reel in rope to support the climber, and the climber must climb to new heights. The players switch roles depending on where they are in the climb. We were able to get these mechanics up and running, and implement an Xbox controller which both players use to play the game, one player using the a,b,x,y buttons and the other player using the triggers on the other end. As I mentioned, this prototype kind of worked, but it was clumsy and it was pretty broken. We had set out to explore climbing/belaying as a metaphor for trust between players, but this interaction doesn’t really start to get at that idea. In general the group felt there was not much merit in developing this prototype any further and to move on. Although it didn’t work out to be anything particularly compelling, it did help us to focus what we want to include in the final experience we create. One of the better features of this piece was the rope that Ben put together, along with the pulling in, paying out mechanic that went along with it. The connection is at the core of the emotional target the group is interested in evoking,and that has directly informed the prototype we are currently working on.

P.S. These are a few games we were looking at.

Solo Joe Rock Climbing

GIRP

Extreme Climbing

Mount Your Friends

Week 7 Update

It’s week 7 and we are coming up to one of our major milestones; we need to make a decision about what we are going to be working on for our final project for the rest of the year by this weekend. Sword Dancer/Rhythm Fencer turned out to be a handy little prototype that came together into a proof of concept pretty quickly, and now the whole team is working on a prototype we are calling Trust Climber. The premise is that you play as one of two climbers who must work together to scale a wall, with one player leading and belaying, while the other catches up to them. We are trying to implement a rhythm element, which will most likely be negotiated by the player/players themselves, as opposed to requiring them to adhere to some underlying beat.

Climbing is achieved by pressing one of the WASD keys to grab hold of nearby handholds labeled with the same letter. When the Climber switches positions with the belayer, they control the rope with the left and right mouse keys. Some of the rocks fall after they have been grabbed in order to make the player keep up a pace of climbing, which we hope will translate into the rhythm negotiation mentioned above. We are also looking into implementing Xbox controller input, with both players using one controller. There is a definite progression that is developing through these last few prototypes, and we are hoping the underlying concepts in this prototype and the last two will all fit together organically into our final idea. The climb continues.

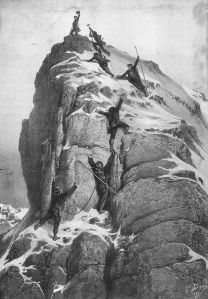

Matterhorn Ascent, Gustave Doré, 1865

Image Source

Sword Dancer aka Rhythm Fencer Game-play Video

Sword Dancing AKA Rhythm Fencer from BABBS Tone on Vimeo.

Music Credit:

Level 1, Zone 1: Crypt of the Necrodancer, Brace Yourself Studios

Sword Dancer aka Rhythm Fencer: Bryan’s Postmortem

Sword Dancing aka Rhythm Fencer Progress

Bryan, Sam and I have been working on very small prototype of a rhythm-based fencing game, which is basically a Necrodancer and Nidhogg mashed-up, albeit a quick and dirty one.

A visualization of the rhythm that Sam hooked up to represent when the player can move, and the basic tile movement Bryan rigged up.

The idea is that all the players’ movements can only be executed if they are on the beat. The goal of the game is to score the most number of points. You do this by landing a lunge successfully. The mechanics include moving right and left, lunging, which you do by default when moving forward, parrying, which deflects a lunge, and feinting which fools a parry. In the cases where a player executes a successful parry or feint, the other player cannot attack on the next beat leaving them open to a lunge, but they can retreat. Lunging in turn breaks through a feint and scores a point.

Lunge, Feint, Parry, Open to attack and Off the best

Player movement is tiled, meaning they can move only one tile every beat. Players may not occupy the same tile, so if there is one tile between them and they are both trying to advance onto it, they will stay in the same position. If both players execute the same move on each other, i.e., lunge-lunge, feint-feint, parry-parry, they are each thrown back one tile so there are two tiles between them so they have space to regroup and choose their next move. After each point each player is reset to their original tile to start a new bout. This is faithful to actual fencing, and to give the players the chance to try out different strategies.

CONVERSATION DRAWER: SAM’S POSTMORTEM

** This post is a follow-up to Bob’s Postmortem **

Line Renderer is awesome. Unity3D provides a built-in Line Renderer that billboards polylines based on given vertex positions. Ben and I had some experience using this to draw trials behind moving characters so we decided to play around with the component a bit more here. Using different widths and alpha values between the start and end vertices, and limiting the number of existing vertices, we generated wakes behind characters that were much more visually appealing than we expected.

I bring up our experience with the Line Renderer because it typifies much of our time working on this prototype. As Bob mentioned, working in the abstract space allowed us to create compelling mechanics and visuals at a relatively quick pace. Conversation Drawer certainly required quite a bit of work over the three weeks we devoted to it, but the rate at which we made visible progress consistently impressed me.

What am I looking at?

Essentially, Conversation Drawer asks the player to carry out conversations in a primarily visual space. The guides her avatar with the mouse cursor and attempts to engage with AI controlled characters in the roles of both follower and leader. When following, the player is tasked with touching ‘points’ that the leader is making and staying within the leaders trail wake to get a speed boost. Following in the leader’s wake allows the player to catch up quickly with a generous speed boost, but a certain number of points must be touched before the player can take the lead. When the player takes the lead, the roles reverse and the player attempts to guide the partner to her own points, eventually letting the partner take lead again. Each time a point is touched or a character takes the lead, both partners gain a small amount speed, as if the conversation is growing in enthusiasm. Failing to touch points our switch leaders eventually slows the interaction down and leads to a break in the conversation.

Complications

I don’t have much else to add to what Bob mentioned as the good stuff, so I’ll spend some time on what I didn’t go so hot. We had to bang our heads against problems springing from both technical complications and playability concerns, as well as some woes of abstract representation. Four problems stand out to me as the major issues, which were resolved to varying degrees.

Looping

Targeting the conceptual metaphor of conversation, made separating the game from a realistic, physical representation of space easy to justify, allowing us to make up the rules of our play space. To solve the problem of the player moving infinitely far away from the hub of AI characters to converse with, Ben implemented a looping system that keeps objects in the world within a given proximity. In the span of a few weeks, developing a spherical world did not seem especially achievable, so we opted to instead teleport objects between world boundaries. Making our space discontinuous for some objects introduced complications that weren’t very surprising, but nonetheless infuriating. Preventing objects from teleporting into or out of the player’s view was high priority, along with correctly transporting the characters’ trails without streaking them across the player’s screen, and ensuring that off-screen character trackers pointed in the correct direction.

Those First 30 Seconds

The first few players outside of ourselves completely missed the entry point to the game because we failed to compel them towards it. In a work like this, I’m personally keen on the idea of minimizing the amount of text, potentially to zero, that we display to the player, so introducing the ‘objective’ with a splash-screen or thick tutorial did not feel like the best option to me. Instead, I added a simple callout animation to the first AI character, in order to get the player’s attention and spark her curiosity. My hope was that player would see the animation, not know what else to do, click the animating object, and watch her unbeknownst avatar move towards the mouse … BAM, curiosity and discovery in the first 5 seconds. The callout even worked out as a nice visualization for AI characters interested in conversing.

Unfortunately the next 25 second were not as well handled. Some players understood that they were meant to follow their large partner, but others missed that completely and thought they were supposed to avoid or attack it. Bob mentioned in his postmortem that people come into games with trained assumptions, and I think the early playtests of this game reminded us that we need to be clear about which of these assumptions break down here, before they interrupt the player. A vaguely outer space-like setting with abstract shapes and one very specific bright, purple line, fulfilled some players’ frame of a space-shooter game. Even those players who knew to follow the partner did not understand how to progress beyond that and were surprised (not in a particularly good way) when they took the lead. If we move forward with this game, we will need to pay special attention to the very beginning of the game, so that we can build upon the early concepts. Players choosing to ignore our direction is far from a bad thing, but players having no idea how to read our directions is much more problematic.

Completing the Metaphor

Similar to our difficultly in communicating direction to the player, we are still struggling with making the gameplay feel like a conversation. The big piece we seem to be missing is facilitating a ‘back-and-forth’ between characters. We’ve made attempts but it does seem to be quite there. The concern is not that every player understand that we are trying to represent conversation, but rather that engaged players feel some sort of non-verbal communication happening between them and their partners, and don’t mistake the interaction as combat.

Following

At the moment the AI characters are little more than vehicles that fluctuate between seeking waypoints and seeking the player. When they hit one waypoint they change heading and move towards the next, sometimes making turns that are nearly impossible for the player to follow. Awkwardness was one of our experiential targets, so this is not always a problem, but the frequency of occurrence was far more than desired. Widening the leader’s wake as it extended made getting the follower’s speed boost easier from far behind, but staying inline while immediately behind the leader remained difficult, with minimal warning time and minimal space. We have yet to overcome this issue, but we are thinking about ways to reveal the leader’s upcoming turns and possibly switching to a Bezier curve path.

Final Thoughts

I like the direction this game headed in, and where it has potential to go. I think this game hits our core priorities and would work exceptionally well as a Master’s Capstone Project. Even with the confusion caused by some of our semiotics and pacing, many players noted that they enjoyed most of experience. If we build this game to completion, we will need to be constantly balancing between abstraction and readability.

Rhythm-Based Fighting Games: A Brief Search

I decided to do quick search of existing rhythm-based fighting games and this is what I turned up, with regards to commercial examples anyway:

There’s Zen Studio’s Kickbeat, which uses its sound track or takes whatever music input you provide and coordinates a series of instantiated would-be challengers to attack you on the beat, unless you smack them down first, which you do by providing the correct input based on the enemy’s color and position.

SNK Playmore’s The Rhythm of Fighters in which you link inputs together to create combos. You have some decision making in that you can block, but it seems mostly to be input matching to a beat.

Then there’s this unexpected item, developed by 505 Studios (?), Way of the Dogg is some oddball game that revolves around input combination to the rhythm of Snoop Dogg/Lion’s opus of rap songs. Very strange indeed.

All of these games look like they take Guitar Hero or DDR are as their inspirations, which is cool, but it just frames the rhythm recognition/input combination mechanics as fighting rather that music making or dancing and so the strategic layer that you find in fighting games is pretty thin. Also, it doesn’t look like any of them have a multi-player element. What we are trying to do with Rhythm Fencer is to preserve that decision making/strategic element, while requiring the players to be on a persistent beat. I’m sure other games must have explored this concept. The research continues.

– Bob

Sources:

Kickbeat Review

The Rhythm of Fighters Review

Way of the Dogg’s Website

Conversation Drawer: Bob’s Postmortem

We worked on Conversation Drawer for a period of three weeks. The prototype started off as a 1 week group prototype that employed a lead and follow mechanic as a metaphor to represent conversation. It was the first prototype that we decided to undertake as a group and it was pitched by Sam, building off of a handful of prototypes we had created over the summer and through the first couple weeks of the semester. At the end of the first week, we definitely had an interesting interaction, but it didn’t really convey the metaphor of conversation, in fact it was somewhat frustrating to play as it was difficult to catch up to the AI who was leading the conversation. A few of the other grads who play tested it for us mentioned it felt more like a game of tag than holding a conversation. The group decided to put some more time into the prototype to see if we could flesh out the experience and convey the central idea of a conversation. We chose to prototype two “conversations”: listening to a story and an intervention. This was to communicate different moods/types of conversation and see what that would look like in the context of our mechanic.

The player (blue) listening to a story from a story teller, from an a slightly earlier version.

What went well:

Working together felt really organic, which was great. It was good to get into the flow of making progress, meeting and reporting, making decisions and implementing ideas. At least for my part, I felt as though I could scaffold onto each group members’ work and incorporate their additions to the project into my own parts while still having a lot of ownership over the aspects of the project I was working on. I think the project generated many productive conversations around expectations of the final product going forward, particularly about the feel and aesthetic that we are trying to accomplish with out thesis work. We came to the consensus that we had to find a working balance between abstraction and metaphor on the one hand, and narrative, figurative elements and symbolism on the other. In other words: yes we want abstraction, but there must be enough in the way of semiotics there for people to grab onto and piece together a concept or pared-down narrative. It never felt like we got to a “stumped” point, which is a high possibility once we begin work on the final concept, and we continually had fun new discoveries and mechanisms to show off to each other, which kept spirits high. The last iteration definitely was starting to come together into a more defined aesthetic direction, and it was a fairly engaging experience. We were able to implement many of the game-play features we discussed and I think showing off the prototype to faculty yielded very useful feedback. One faculty member remarked that the interaction was fun, which while not our primary emotional target, is a welcome by-product. Another observed she felt “kinda sad” when one of the conversation partners took off without her. This is important as part of our research is focused on relatedness as a motivation in games, and its emotional ramifications.

The player (blue) leading the green A.I. in conversation, guiding them to various “points” and “details”.

What didn’t go as planned:

Taking into account that this was only a three week prototype, one of the biggest problems at the end of the cycle is that it doesn’t seem like people were receiving the experience as a metaphor for conversation, which was part of the intention of the prototype. There is a distinct difference in expectation when people interact with a game as opposed to a piece of conceptual/contemporary art. With an art piece the audience often expects to spend time contemplating the symbols in the composition and come to a personal understanding and relationship with the work, which usually has no “correct” interpretation. This is of course different than religious or overtly propagandist genres of art. Interaction with video games does often include this personal relationship/interpretation aspect, but it is also expected that the game will explain itself/explain how to play it in some way. The challenge is to encourage the interactions we hope the player to experience, while not forcing the player’s hand, or being to heavy-handed and giving away the underlying metaphor. In any case, I think it is possible that that we can convey the metaphor given a lot more iteration and feedback.

That being said, the primary goals of out project do not overtly state conveying a metaphor, but rather hitting an emotional target other than fun, so we need to discuss how important this goal is to the final product. It is something that I am personally interested in; I think it is interesting when games play in that space between game/sport, interactive narrative and art piece. I observed that the faculty who tried our prototype seemed curious and engaged, however a few who got to the second part of the prototype (the intervention) were frustrated by the speed of their partners and the difficulty of catching up to them. Frustration is a target we should think about exploring, but it must be intentional. I think the game-play features were there, and they were interesting, but they didn’t exactly do what we wanted them to do, and so we should have put more effort into iterating that and making sure that component really worked. I think as a program that owes it’s lineage to CS, we have a distinct technologist bent, and we can get a little caught up in getting something to work. Don’t get me wrong, that is awesome and it feels really great when you get a feature/piece of tech up and running. I definitely have felt that way over the last few semesters. However, we need to be more aggressive about keeping sight of the core game-play first. It’s something I think we are improving on, and I in particular have a tendency to want to work on the aesthetic layer, but we really need to keep that in focus. For example, upon reflection the “drug points”, which the player would pick up and cause them to shoot a burst of particles for a short time, was very cool to look at, but may not have actually added to conveying the feel of an “intervention” style conversation.

Final Thoughts:

Overall I think it was a very good exercise. It’s the sort of thing I wish we had had more time to do last semester honestly. I would have much preferred working on one or two projects at a time for a period of a couple weeks to a month, as opposed to four or five semester long, large projects. I just didn’t feel like I had a handle on any of them. Anyway, I think Conversation Drawer is a strong contender for a final concept, but as Bryan pointed out, we should definitely have more prototypes under our belts before the end of next week so we have more options and expertise.

– Bob